hot jupiters get even weirder thanks to a disco ball planet

Gas giants orbiting their parent stars just keep getting weirder and weirder.

When massive gas giants were found in alien solar systems, orbiting their parent stars — or maybe, in some cases, their stellar captors — in a matter of a few days or hours, starting in 1995 with 51 Pegasi b, astronomers were scratching their heads. It seemed so unlike our own solar system where rocky planets orbited a star up close, and icy gasbags floated in the outer reaches and produced more heat internally than from the starlight that hit them. But now, we’re sort of used to them since we found so many thanks to how easy it is to notice them by measuring the hefty pull they exert on their suns, and had time to accept that yeah, that’s just a thing our universe does.

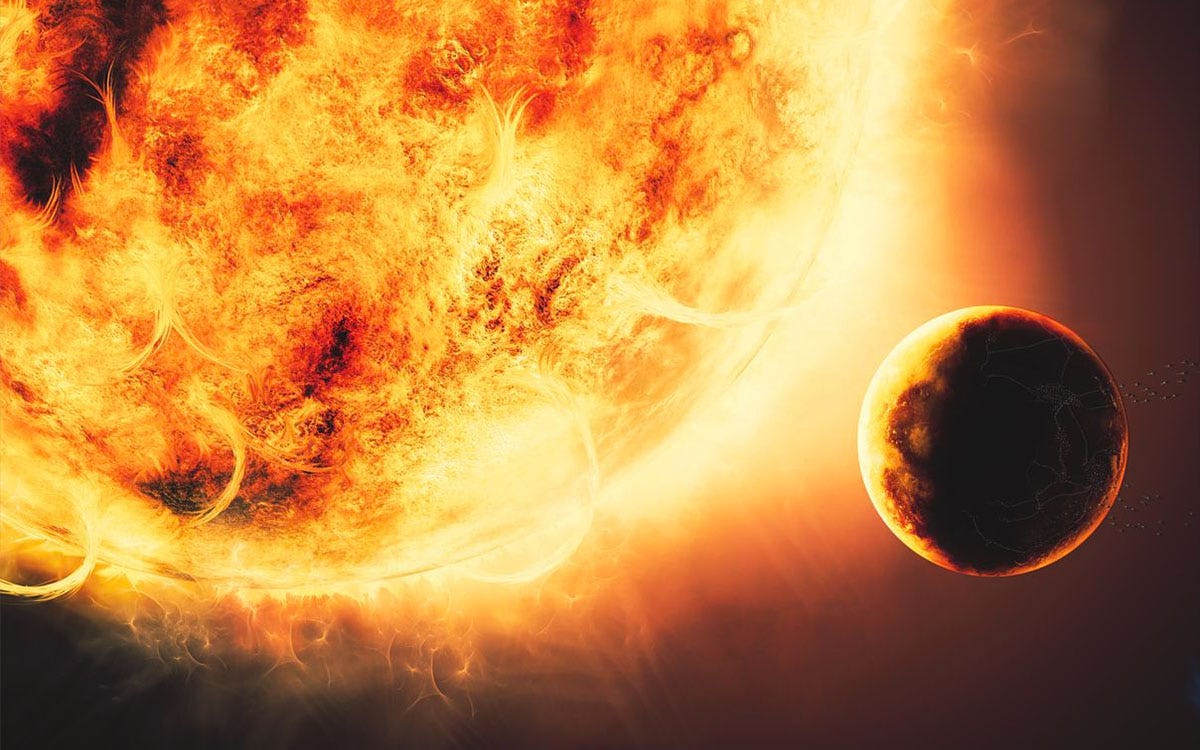

At this point, we’ve seen “naked Hot Jupiters,” planets that look like stripped down cores of gas giants, their atmospheres completely blown away by the solar winds. We’ve seen a gas giant seared to 4,000 °F, or 2,200 °C on its day side, facing the sun storms triggered by its own mass that turn its clouds into plasma until the end, the star’s gravity well literally preventing it from spinning around its own axis. (By the way, the record for hottest Hot Jupiter is KELT-9b at 7,800 °F, or 4,300 °C.) We’ve even seen a few planets that resemble a comet as they plunge towards their imminent fiery deaths, millions of tons of gas billowing into space every second.

But now, we’ve seen a new kind of Hot Jupiter, a disco planet where titanium silicate clouds reflect 80% of incoming light as the surface burns at 1,800 °C, or 3,300 °F. In a way, it’s reminiscent of Venus, which reflects 75% of incoming light while broiling at 475 °C at ground level. Yet Venus’ thick, dense cloud cover acts as an insulator which traps heat from the Sun. On the newly discovered planet oh so poetically named LTT 9779 b, it’s the heat from the star it orbits every 19 hours incinerating the metals and silica floating in its clouds on its permanent, tidally locked day side, which then reflect the incoming light by virtue of the gas being metallic.

It’s almost as if the planet is fighting back, pushing away as many rays as it can while being mercilessly fried by its Sun-like star. Right now, it’s about the size of Neptune, but it will eventually be whittled down to an exposed rocky core several times more massive than Earth. We don’t know exactly how it ended up with a year shorter than our day, but we suspect that protoplanets jostle for a stable orbit and rapidly forming gas giants in the outer reaches have to plow through the dust and debris from which solar systems are born. If they end up in very eccentric orbits or form too close to the star, they may be doomed to spiral right into their suns.

That’s the fate we think Jupiter avoided early on, and its powerful gravity well helped the other three gas giants find their bearings. But if the oversized siblings came a bit too close to each other, or the protoplanetary disk would’ve been denser, we may well have ended up with a Hot Jupiter in our system as well. Only we wouldn’t have been around to observe it since it would have pushed baby Earth out of the way as it kept spiraling closer and closer to the Sun, either sending it into the interstellar void as a rogue world, or unceremoniously hurled it into our home star to be reduced to a trail of radioactive glass, then plasma.

So, in summation, yeah, we missed out on spectacular light shows around the clock for astronomers, but we got lucky enough to exist and have astronomers to admire them elsewhere and learn more about the weird reality we inhabit. And yes, it’s one that includes planets that act like disco balls in the night sky. Go us, right?

![[ world of weird things ]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!V-uR!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F93728edf-9a13-4b2b-9a33-3ef171b5c8d8_600x600.png)