is our universe really twice as old as we think?

A new paper making big waves says that the cosmos is 26.7 billion years old. The catch? It relies on phenomena we've never seen before.

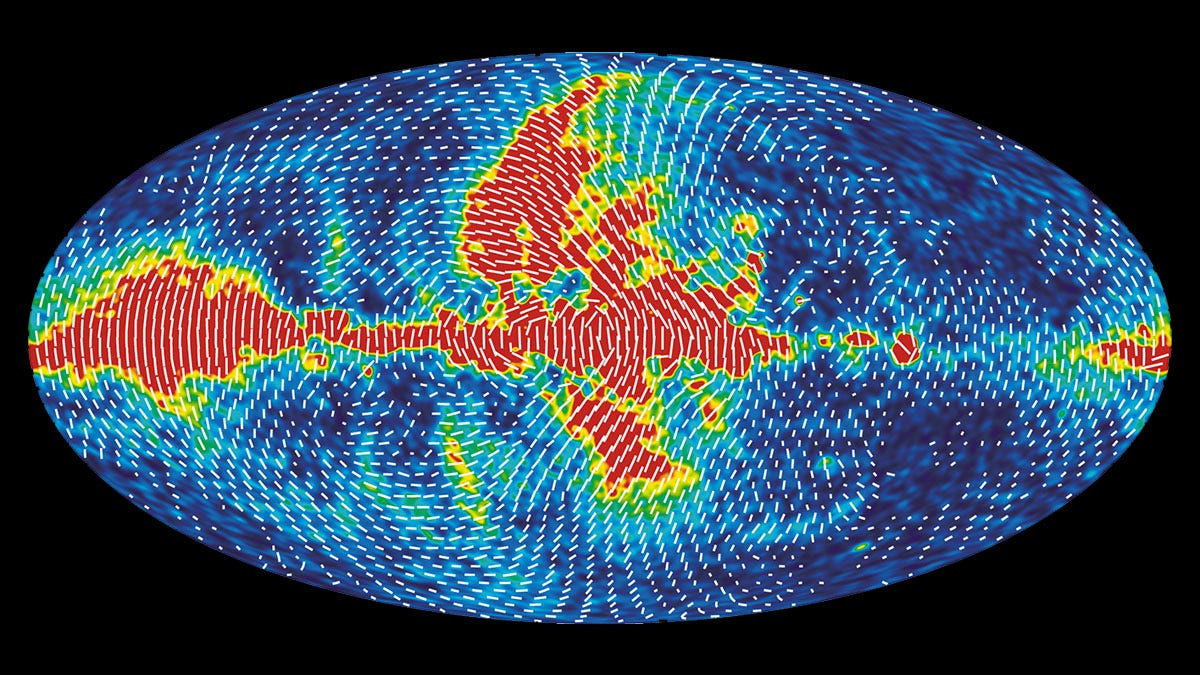

For thousands of years, astronomers debated the exact shape, size, and origin of the universe. Until about a century ago, it was assumed that the cosmos was static and eternal, a never-ending web of galaxies that may change and evolve on their own in a vast, infinite realm that always existed and always will. Then we discovered redshift and the fact that other galaxies were moving away from us at an accelerating rate, as well as the CMBR, or the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation, the shockwave of the Big Bang. Following the evidence where it led meant that the universe was not in fact eternal but just around 13.8 billion years old. And it was rapidly flying apart.

Now, a paper from a Canadian physicist is claiming that no, we have it all wrong and a number of objects like very large galaxies or stars seemingly older than the current age of the universe mean it’s at least twice as old, and the reason why we think it’s a lot younger is because we’re not accounting for two small but crucial phenomena on the cosmic scale: tired light and coupling constants. While experts largely dismissed it as insufficient to turn cosmology on its head, it’s gotten a great deal of attention since Bromaster General Joe Rogan and His Space Kareness Musk decided to promote it on Twitter despite the scientists’ objections.

Since this particular duo tend to have a knack of making bad ideas popular, we have no choice but to discuss why a scientist would think that the universe is 26.7 billion years old and why he’s probably wrong. And to do that, we need to start with a quick review of the basics: why do we think the universe is expanding, and how did we get to the current age estimate of 13.7 billion. This isn’t a number picked out of a hat, but the result of decades of observations, weighing the universe to understand what it’s made of, and yes, analyzing the patterns in the CMBR, and how they relate to the all the observations of stars, galaxies, and supernovae.

how do you check a universe’s birthdate?

So, first things first. We know that the universe has matter and that matter creates stars, planets, and galaxies, and a whole bunch of dust and debris. The vast majority is effectively empty space, which has its own weird things going on, and we also have this weird stuff holding galaxies together that we don’t understand yet. How do we know all of this for a fact? Well, we can see stars, planets, and galaxies. And we can also detect all sorts of energetic phenomena like cosmic explosions which interacts with all that matter and determine its density, as well as the effect all that mass has on the shape of the space around it, and how and where that matter is moving.

We know that the universe is expanding because we understand redshift, the fact that light loses energy as it travels, appearing redder when it moves farther away from us as the distances between the peaks and valleys of its oscillations become longer and longer on cosmic scales. Since redshift is predictable by the laws of physics, we can look at Type Ia supernovae which are crated by the same exact phenomenon and all have almost the same energy and explode with the same brightness, then compare how bright we expect them to be to how bright they actually appear in far off galaxies. This tells us how far away their galaxies are and the rate of cosmic expansion.

On top of that, we can also look at the motion of galaxies and figure out how much all the stars and dust in them have to weigh to account for their velocity, which make it kind of obvious things don’t all up and no matter how much we try to get rid of it, we end up with dark matter and dark energy to explain the observations. So, when we plot the masses and distributions, then compare them to the detailed CMBR map — which tends to match this distribution of mass quite closely — we end up with just under 13.8 billion years to explain how things got to be the way they are throughout the cosmos. It’s not an ironclad date, true, but neither is it just a wild guess.

“all we need to do is rewrite physics”

All of the above can be summed up as the ΛCDM model, the official consensus on the age, composition, and physics of the universe as far as we understand it today, and so now that you know the context, we can talk about what this new paper says our model got wrong and what “tired light” and “coupling constants” actually mean. To get to the new age of the universe, the paper’s author, Rajendra Gupta, combined two famous but discarded proposals into a new theory of how light travels across the universe and how different forces interact with each other on cosmic scales. His main argument is that if he’s correct, the cosmological picture we see is greatly distorted.

First up is the notion of tired light, proposed by Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky in 1929 to explain why the universe was expanding according to Edwin Hubble’s observations, which shocked cosmologists. He posited that photons collided with other particles at much higher rates than we think and lost a lot of energy traveling long distances, the scattering making objects look a lot redder and further away. But he was never a fan of his own idea, noting that distant objects would look blurrier than they actually are, and that some of our observations of gravitational lensing and galactic evolution just wouldn’t be possible if tired light was a thing that existed.

That brings us to coupling constants, an idea from theoretical physicist Paul Dirac that says the interaction between subatomic forces may have evolved over time. Just like Zwicky with tired light, he wasn’t exactly dead set on this, it was just a hypothesis he was entertaining and one we also have reason to believe runs contrary of what we see out in the universe based on studying 7 billion old molecules of alcohol in deep space. If billions of years haven’t changed the behavior of forces holding molecules together, it’s almost certain that whatever shift happens over time is too slow to let us modify a currently viable cosmological model by a factor of two.

chasing after mysteries across universe

All right, you might say, if Gupta wants us to ignore the laws of physics as we’ve been able to observe them for at least the past century are wrong and just agree with him that Zwicky’s and Dirac’s shots in the dark to explain away the expansion of space as seen by Hubble are right, he must have had a good reason, right? Well, yes and no. In his thesis, he argues that several galaxies look too large and mature for some of the very first cosmic objects, as well as pointing to Methuselah stars, which at first blush may appear to be older than a 13.79 billion year old universe. Surely the ΛCDM model has to adequately explain those to remain relevant, right?

Believe it or not, one Methuselah star is actually in our cosmic backyard, within an interstellar humanity’s easy reach at a mere 190 light years away, and it’s this star in particular that seemed to be anywhere between 22 million and 2 billion years older than the universe itself. Astronomers looked a lot closer since these estimates were wildly unreliable, and started narrowing down the various indicators of star age using the Hubble orbital telescope. After nailing down the distance and oxygen lines over a decade, they found that it was really around 12 billion years old. Remarkable, ancient, but well within the realm of plausibility.

As for the seemingly mature galaxies less than 800 million years after the dawn of time found by the JWST telescope, that one is, indeed a bit of a head scratcher. But we would do well to remember that we’re still not entirely sure how galaxies form, as well as what happened in those first few hundred million years. JWST has also seen evidence of “black hole suns” that could be a shortcut to supermassive black holes forming around 320 to 400 million years after the Big Bang, which would also create heavy, stable galaxies in record time. In short, the jury is still out on that one because we lack sufficient data to declare them a real problem for ΛCDM.

“and now, we apply occam’s razor”

Hold on a minute, the critics object. Why are we trying to fit the ΛCDM model with so much fervor? Doesn’t it make sense to challenge it? Of course it does! If you manage to break cosmology, there’s even a Nobel Prize and a million dollars placed as bounty on modern astrophysics’ head for you to collect. Yet, the problem with Gupta’s paper, just like with the papers of almost everyone who’s tried to overturn the ΛCDM model, dark matter, and dark energy, is that they focus on particular poorly explored and low confidence edge cases and observations to the detriment of the rest of the universe, which is now full of odd contradictions and phenomena under their new models.

What good is it if you turned back the clocks to the dawn of the previous century and just accept guesses from two prominent scientists — who were simply playing devil’s advocate to keep a static, eternal universe as it was being disproven — just to plug in new equations to solve problems we’re not sure are real problems and jumble up the 99.9999% of physics we’re still extremely confident about? You do get a headline out of it and a virtual fist bump from the guy who’s ruining vaccination and a guy who’s ruining social media, but leave a mess of a theoretical universe for others to clean up. And in science, that means you probably did something wrong.

See: Gupta, R. (2023) JWST early Universe observations and ΛCDM cosmology, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stad2032

Labbé, I., et al. (2023) A population of red candidate massive galaxies ~600 Myr after the Big Bang. Nature 616, 266–269, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05786-2

Ilie, C., Paulin, J., Freese, K. (2023) Supermassive Dark Star candidates seen by JWST, PNAS 120 (30) e2305762120, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2305762120

![[ world of weird things ]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!V-uR!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F93728edf-9a13-4b2b-9a33-3ef171b5c8d8_600x600.png)