why math says there’s no such thing as a true meritocracy

According to pundits and politicians, we live in a world where talent and reward go hand in hand. But basic statistics says that’s simply not possible.

For the last century, we’ve been told that talent and ability are appropriately rewarded by society, that we live in a meritocracy where our aptitude and skills define how well we do in life. It’s what we learn in school and what politicians, pundits, and seemingly ubiquitous motivational speakers blare around the clock. But there have always been some glaring problems with this notion, odd facts that never add up if we look at the world with a critical eye, but are nevertheless defended with blanket statements that casually write off vast groups of people to sweep these inconvenient statistics under the rug as not to ruin the accepted narrative.

Consider the bell curve. Every human, and every population falls somewhere along it, with the vast majority in a middle 70% of skill and talent. If we lived in a meritocracy, we should expect a more or less even distribution of men and women across all racial and ethnic groups becoming wildly successful as the 20% of each group get outsize rewards. Instead, in the U.S,, the top one percent have as much wealth as the bottom 90%, nearly 9 in 10 of them are white, and more than 8 in 10 are male. But white men number less than a third of the population, and white people overall are just over 60% of all Americans. What happened to the rest of the demographic pie?

A true meritocracy blind to race, gender, and upbringing should be way more diverse since statistically, the top quintile of the remaining 69% of all Americans who are not white males should be regularly making it to the top of that wealth and income heap. Obviously, there’s more going on here than pure merit just by statistical inference. We can further prove it with modeling that shows us what would happen in a meritocracy where everyone is truly treated as an equal, generational wealth is not considered for the sake of a truly uniform starting line, add a dash of luck, then compare the results to what we see today.

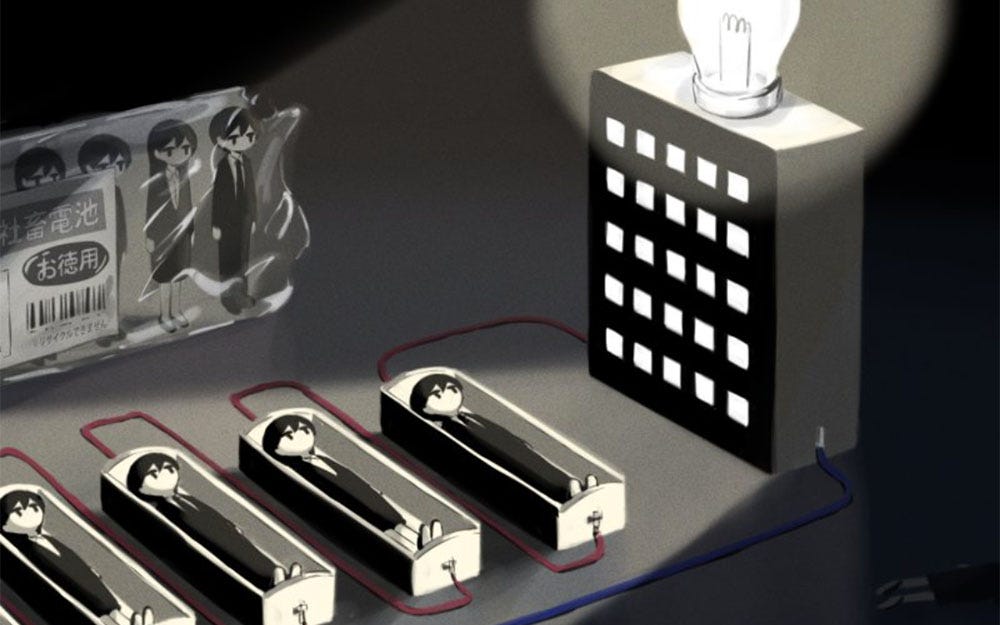

Five years ago, a team of Italian researchers occupied with the same question created a statistical model to do just that and figure out if a meritocracy is even possible in an absolutely perfect world with perfectly equal opportunity for everyone, the only factor left up to the universe being pure, blind luck. The simulation was populated by virtual agents allocated a certain amount of skill based on where they fell along a bell curve, then had them spend the next 40 years hard it work while a background process was generating lucky and unlucky events. Lucky events doubled an agent’s wealth, more if they were in the top quintile of performers. An unlucky event could halve it.

why luck beats talent every time

At the end of the simulation, the researchers tabulated the agents’ wealth distribution, designed to mimic what we see in the real world, and analyzed which agents became the virtual equivalents of one percenters in their experiment. To their lack of shock, it was almost never those allocated additional talent, but regular individuals who just so happened to get lucky. Which makes perfect sense because they were the majority of the agents to whom good and bad things happened, so those who had the most lucky breaks would have to be from the average population, mathematically speaking. They just had to be in the right time and the right place, and usually were.

Now, this study has some obvious limitations and the fact that all of its agents started with the same amount of capital and opportunities is far removed from the real world. But it does a great job of capturing how important it is to have good luck to succeed. Born into an ethnic majority? Talented at something in high demand? Noticed by the right people and got that big promotion over or alongside the boss’ kids? Received a vast inheritance? Your parents know influential people who can vouch for you or get you a job? Every one of these lucky breaks is critical in achieving long term success and wealth, and we actually know this quite well.

This is why the children of the well-to-do go to certain schools, are taught to network and make certain friends, and pushed into internships that could give them an edge in landing a lucrative or highly prominent job. Much of “upper class” upbringing is about creating as many opportunities as possible for new generations to come across, then to capitalize on even the slightest bit of luck, to be there at just the right time to seize an opportunity before someone else even knows it exists. If we lived in the kind of fair and blind meritocracy we’re told we do, and honestly believed in it, there would be no reason for high end boarding schools and upper-class clubs to exists.

Talent, no matter where it came from, would dominate, so the emphasis would be on developing some skill in which a child had the highest aptitude as much as possible for guaranteed reward when they hit the top 20% on the bell curve or higher. Instead, we constantly contend with hiring biases, market trends, personal connections, and intergenerational wealth that puts a firm glass floor under the family’s progeny. So, in other words, people who seem off-the-charts successful and to get every promotion or chance to shine aren’t that way just because they’re skilled enough to dominate in doing the actual work.

how to cash in at the casino of life

What really happened is that the one percent and their families went out of their way to ensure they had as many irons in the fire as possible, elevated their profiles, then leveraged what resources they had to get the slightest edge, to be one of the tallest trees in the forest when lightning struck. Only then could they put their talents — if they had any — to good use. Which brings us back to the model. If we know that luck is the defining factor in wealth and success, what’s next? After all, in a world of flesh and blood humans with more than 300,000 years of history behind them, it would be pretty much impossible for a true meritocracy to exist.

Yet, it’s equally absurd to think that we can say that someone worth a billion dollars is somehow objectively a billon times more talented than someone in debt as if we can compare talents in an apples-to-apples way. Based on the model’s recommendations, the best way to ensure more people succeed is to simply give more people chances in a field where they show aptitude and allow them to catch some of those lucky breaks they’re currently denied. Given the tiny differences in human genes and the fact that all of us fall along similar bell curves, odds are that a random person would do just as well as a random scion from a wealthy family in the same job.

The fact that the wealthy often install their spawn rather than hiring lower or middle-class applicants in prominent posts tells you just how little faith they have in the idea of a meritocracy they espouse. Most importantly, societal acceptance that wealth is more like winning enough hands in a casino than anything else, that some of us have more chips than others to get more chances to win, and that talent only takes you so far without luck, would change quite a few policies around education, healthcare, and assistance programs. More importantly, it will force us to accept that no matter what some seem hell bent on believing, everyone deserves a real, fair shot at success.

Again, it’s wildly unrealistic to think that we could ever give everyone the exact same starting point like the simulation does. The outcomes will still be unequal, but at least we’ll know that we evened the playing field and made life a bit more fair and bearable for everyone. Still, in the minds of far too many there are natural hierarchies headed by people who are just naturally better than others and if they were to ever make it to the top, well, that means they’re also superior specimens. Their desire to feel special overrides their empathy, if they had any to begin with. But armed with research and models, we can at least expose these self-aggrandizing lies for what they are.

See: Pluchino, A., Biondo, A.E., Rapisarda, A. (2018) Talent versus luck: the role of randomness in success and failure. ACS, DOI: 10.1142/S0219525918500145

![[ world of weird things ]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!V-uR!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F93728edf-9a13-4b2b-9a33-3ef171b5c8d8_600x600.png)