yes, it's really hot. yes, it's really bad. yes, it's going to get worse

Global warming is making heat weaves in already scorching years much worse. And none of us are ready for just how nasty things could get.

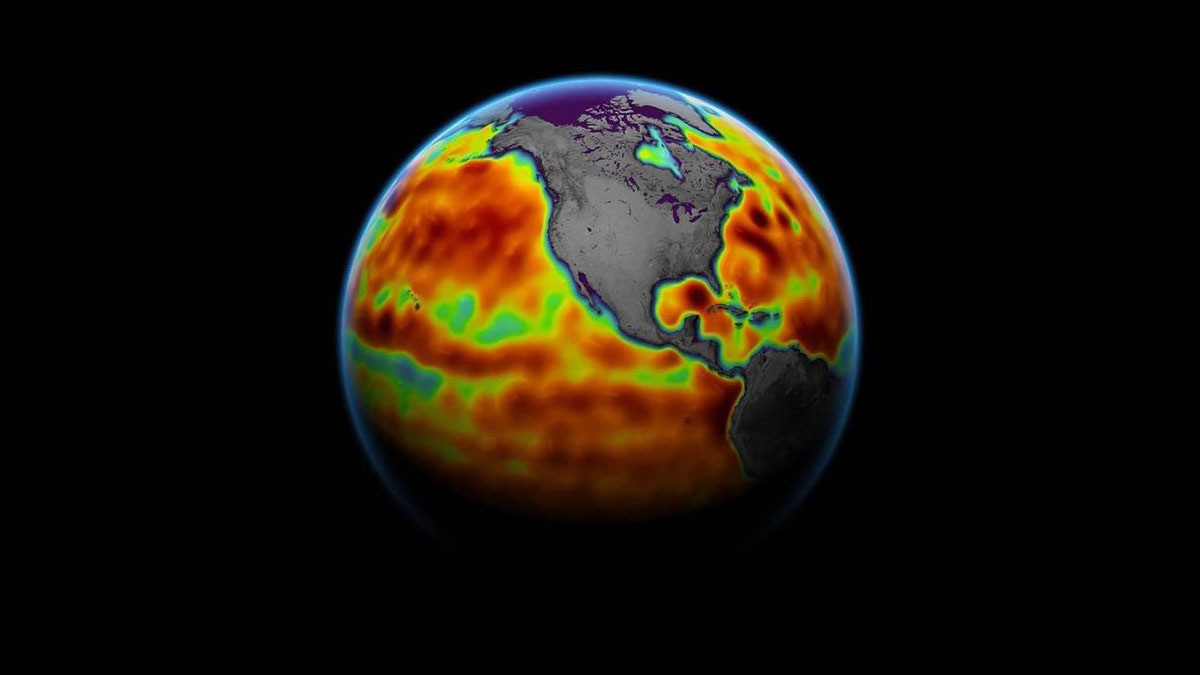

You probably don’t need a reminder that it’s a little too toasty for comfort right now if you live in Europe, North America, North Africa, or East Asia. Here in the Southwest U.S., triple digit days seem to have settled in for the foreseeable future, and you plan your day around the afternoon blaze. Part of the reason why it’s so hot is a strong El Niño warming the Pacific Ocean. In the cycle of temperature high and lows, this was going to be a hot year no matter what. But global warming and climate change are making an already tough peak in the cycle worse, with the very first Thursday of July marking the fourth consecutive hottest day on record since 1979.

Even worse, we’re not done yet. July is typically the hottest month of the year and we may still have a few records to set. Our cities’ infrastructures are woefully unprepared for this onslaught, and while next year is very likely to be cooler, it won’t be cooler by much, as global averages continue trending upward year over year while we continue to build for a planet that’s two to three degrees cooler than it actually is. In fact, there were similar warnings around this time last year, as heat waves like much this wreaked havoc and killed tens of thousands in Europe and Asia by heat exhaustion and various health complications affecting the heart and brain.

Going forward, more and more places across the globe could start seeing dangerous wet bulb temperatures during their summer peaks, as prolonged intense humidity of 99% or more combines with 36+ °C, or 97+ °F days to make it impossible for people to cool down fast enough to avoid fatal heat strokes. Since these are hardly unusual conditions and two thirds of the world doesn’t have air conditioning and may need to be out to work during the summers’ worst, that’s going to be a serious problem, and millions are going to suffer in the coming years. It’s even possible that entire nations will become nearly uninhabitable for months at a time.

We don’t even have to look at future trends to see people suffering from the extreme heat. In June, three construction workers toiling in the Texan sun died of heat stroke, and that’s before Texas Governor Gregg Abbott’s new law banning mandatory water breaks through local ordinances goes into effect in September. If existing breaks are still deadly for workers in summertime, just imagine what doing away with them will do, and what will happen in other regions where those in power also don’t care if you live or die, and will make absolutely no effort to keep people cool, hydrated, and safe. The future is less summer fun and more summer survival.

And we haven’t even gotten into summer storms, which will be getting stronger, less predictable, and more frequent, fed by broiling, longer heat waves and warmer ocean temperatures. Over the last 50 years, storms killed 2 million people and cost us $4.3 trillion worldwide, and the events increased five fold in frequency year to year. Just for context, the U.S. saw 31 storms causing $1 billion or more in damage in the 1980s. In the 2010s, that number was 128. Last year, it was 18. If the 80s were just as intense as today, we would’ve seen 200 major storms costing $6.9 trillion in that decade rather than the 341 storms with a price tag of $2.5 trillion we saw in the last 42 years.

Yet, there is still hope. Despite the frequent inaction, if not downright regressive and malicious policies of our leaders, green projects are exploding around the world. Even the most publicly obstinate states and countries may scoff at “green Marxism” but in private, aggressively lobby for every clean energy project they can get. On top of that, the more obvious the ever-accelerating effects of climate change become, the more denialists sound utterly detached from reality, demanding that you refuse to believe your own eyes. And at some point, reality is going to have to win because while we as a species often flirt with danger, very few of us are fine with our own extinction.

![[ world of weird things ]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!V-uR!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F93728edf-9a13-4b2b-9a33-3ef171b5c8d8_600x600.png)